Many of us do work that is inherently and inarguably valuable. There is an intuitive and logical connection between the work we do and some larger, later good. Yet our actual, direct impact is hard to define or know. For years, these programs have been funded based on their face value, but many funders now require more. Programs that work to prevent bad outcomes, build protective factors, build awareness and knowledge, or meet basic needs often struggle the most to articulate and measure their impact. Here are the most common challenges I see and the strategies I recommend for addressing them.

Challenges

Future-Telling

Prevention programs struggle with a common challenge. You can’t know what might have happened if your program didn’t exist. You can’t know what didn’t happen because your program does exist. So how do you measure what you prevented?

The First Ripple

The image of throwing a stone into a pond and watching the ripples grow and push outward often describes what we hope our programs accomplish. We throw the stone. We are responsible only for the first ripple. We hope and believe that our ripple creates others. But we don’t know for sure. We don’t have the resources or the time to follow-up to measure long-term outcomes.

One of Many

Many of our programs target large, complex social problems that have many causes, contributors, and influencers. You are only one piece in the puzzle. You contribute to the solution, but you alone do not offer or create the solution. It’s difficult to measure the impact of our contribution when so many other factors are at play and outside our control.

Strategies

Each of these challenges can be and are addressed by certain evaluation designs and strategies. Some programs use randomized control trials, quasi-experimental designs, and statistical methods to isolate the impact of their programs and know the strength of the relationships between their interventions and any effects. However, these are complex and often require significant resources, expertise, and time, which the average nonprofit doesn’t have.

Instead, I recommend organizations create evidence-informed Theories of Change.

Theories of Change

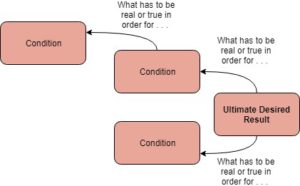

A Theory of Change is a visual representation of the chain of conditions that are necessary and sufficient to create a desired impact. They are created using a backwards-mapping process that begins with the ultimate desired result and then surfaces your beliefs and assumptions about what has to be real or true in order for that change to occur. You create a Theory of Change by working from right to left, as the arrows below depict.

You read a theory of change left to right, and the arrows then point in that direction to show the sequential or causal relationships between the earliest conditions at the far left and the ultimate desired result at the far right.

Many people use the terms Theory of Change and Logic Model interchangeably, but I do not. They are related tools that both inform program design and evaluation efforts, but they have unique purposes and value, in my opinion. Here’s how I compare a Theory of Change to a Logic Model:

| Theory of Change | Logic Model | |

| Maps . . . | A process of change | A program |

| Focuses on . . . | Everything in the context | Everything in your program |

| Includes . . . | Outcomes only (conditions) | Inputs, Activities, Outputs & Outcomes |

| Illustrates . . . | Causal chains of conditions | Program components |

| Communicates . . . | How | What |

Theories of Change are often complex, comprehensive, and – quite frankly – messy. They represent the multi-faceted web of conditions, factors, and influences that impact a population, issue, or problem. Logic Models, on the other hand, tend to be more focused, linear, and clean. Here’s an article from Tools4Dev that expounds on their differences and includes this great illustration of their relationship.

Research

Your organization can create a Theory of Change that documents your assumptions and beliefs about how change happens, so you can illustrate how the stone you throw into the pond contributes to those later and larger results or how your intervention is one of many that work together to create a shared result.

But you can strengthen your Theory of Change by grounding it in research. In many cases, others with more resources, time, and expertise have conducted complex evaluation and analyses to prove the relationship between conditions. Use their learning to test and validate your assumptions. If someone else has proved that A à B à C, then you just need to measure your effectiveness at impacting A to make a reasonable argument that you contribute to or influence C, without you having to directly measure C or prove the relationship yourself.

If your organization has an intern or practicum student, this can be a great assignment for them, as they have access to academic libraries that you might not. In some cases, members of your staff – as alumni, field instructors, or adjunct instructors of universities – also have access to academic libraries.